Adrian Lorenzana

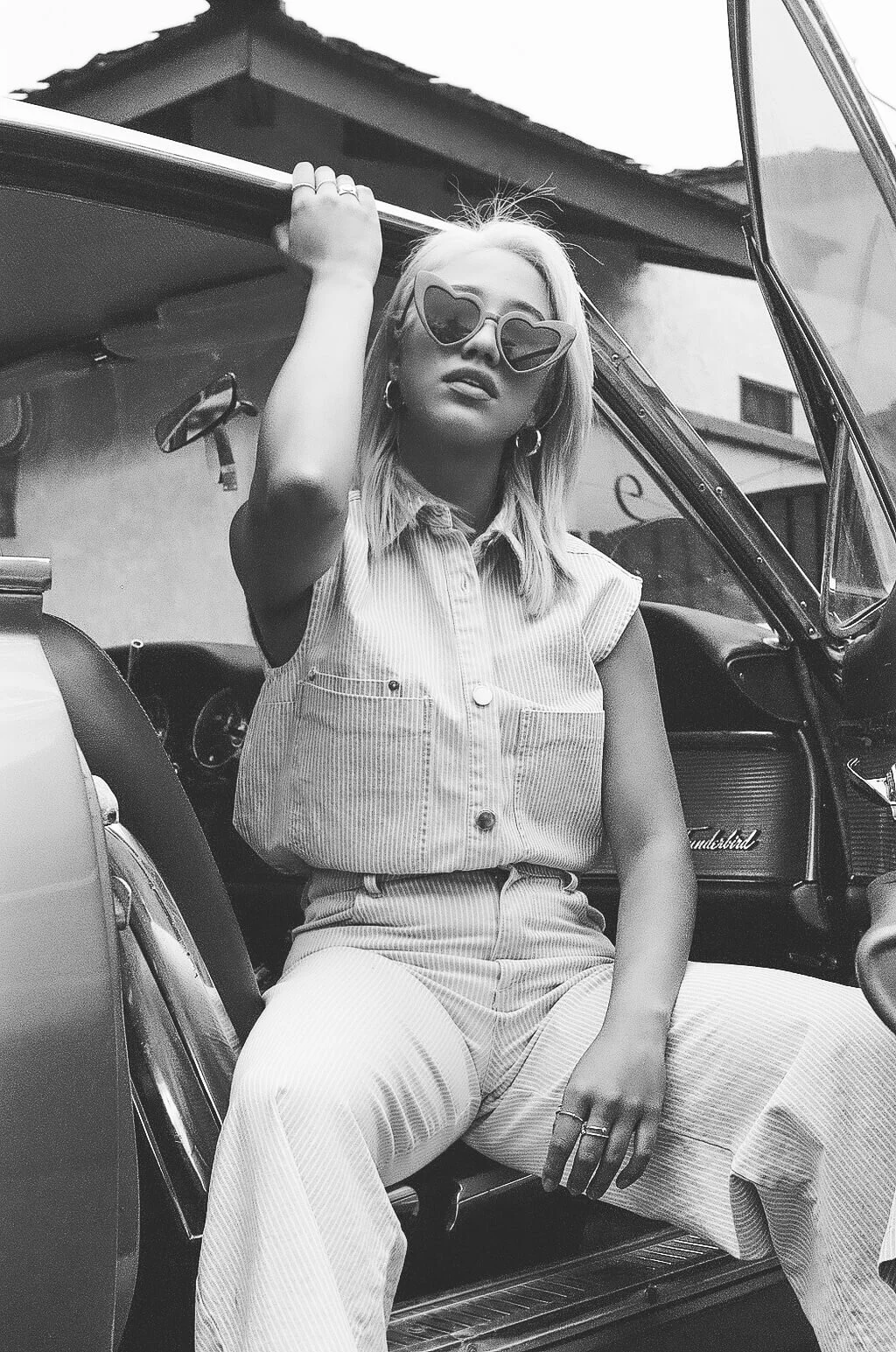

For a captivating glimpse at the ongoing film photography renaissance, look no further than the work of Adrian Lorenzana Villegas, the creative known online as @smallicedcoffee.

After a short stint in San Antonio, Texas, Adrian moved back to LA with plans to become a tattoo artist, eventually committing to graphic design, digital marketing, and a revitalized interest in vintage-style film photography. “It was like discovering life all over again,” he says. “I went from Texas suburbs to North Hollywood, and I had a bike, so I was going everywhere and carrying a camera with me at all times.”

Over the last few years, he has grown by leaps and bounds, creating stunning, often risqué portraits both hazy and clean, seductive and innocent. The inspiration is timeless: muscle cars, classic tattoo designs, and the unique aesthetic of 1970s-era Playboy magazines.

And despite a portfolio chock full of collaborations with some of the biggest up-and-coming models and musicians in the greater LA area, the 23-year-old remains grounded. Reflecting on his work and the friends he’s made along the way, Adrian makes a point to dispel the social media myth, lavish lifestyle, endless parties and all the rest. “I’ll get these comments like, ‘Oh, I wish I had your life,’” he says. “And I'm like, ‘… I just work all the time.’ I’m either shooting, driving, editing, or sleeping. It’s not that interesting.” So it goes.

For the full conversation where we talk Playboy mag inspo, shooting BTS for Tyga music videos, Mac Miller’s lasting impact on fashion, and of course, iced coffee, read on.

When we last spoke, you mentioned going for “photo walks” around Long Beach, California. What’s a “photo walk,” to you?

It’s street photos! Basically you just go, “Okay — I like this area. I'm going to walk around and find things that I like.” Sometimes people will stand in one spot for a few hours, just to get different lighting. Personally, I like to drive down to Long Beach, ‘cause there's a bunch of classic cars in that area. I shoot portraits, primarily, so sometimes I want to make photos that get away from that for a bit. I go almost every other weekend, take photos, hang out, and get a slice of pizza. I feel like there's a sense of community in some parts of Long Beach that doesn't exist in other places in LA, because it’s so spread out.

Seems like you keep it pretty casual when it comes to finding inspiration.

It definitely varies. I like to look through a lot of vintage Playboys, like 1970s Playboys. For me, that was the best version of what they were doing. I don't know who the creative director was at the time, but whoever it was … they did a great job. That's what I kind of lean into for inspiration. But ordinarily when I’m shooting with a friend, I don’t want it to be crazy, or stuck in a studio stuck on time. I come into shoots with an attitude of, “Hey, I haven't seen you in a few months — let's just catch up and take some photos.”

How’d you get into that 70s Playboy era?

I used to work at a tattoo shop, and when I was there I’d look through all the books they had. Most tattoo shops will have a huge bookshelf they use for reference. So the shop I worked at had a ton of Japanese design books, with a lot of shibari, but they also had a little section of old Playboys.

Playboys are pretty key because, as an artist, it gives you ideas for posing, and also for women's faces. Artists will be doing, for example, a study of a woman's face, and it’s easier to go into those old magazines and find and trace something like that. I saw so many people coming through those doors and getting tattooed, and all that definitely inspired what I wanted to make. It made me want to shoot people. They're just … interesting.

What was your role at the tattoo shop? And how did you start working there?

I was shop help. I would just clean up. My brother’s a tattoo artist, and one day he was like, “Hey I have a really busy week and my station is a little dirty — can you head in and clean it?” I was 15 or so, just visiting him during the Summer for a month and a half while I still lived in Texas. I showed up at the job, cleaned his station, and the owner was basically like, “Hey do you want to work here, hang out, clean up after people? They’ll tip you.” I was a young kid and I just said, “Sounds great.”

Eventually I went back to Texas and I had to break it to my mom: “I'm moving back to California.” My brother and sister both still live here, and my brother offered me an office space in his one bedroom apartment. I literally had two bags in my backpack: one with camera gear and one with painting supplies.

Moving back to LA, it was like discovering life all over again. I went from the suburbs of San Antonio, Texas to North Hollywood, California. I had a bike, so I was going everywhere, and carrying a camera with me at all times. My brother's a tattoo artist in Studio City, and as I said, that tattoo shop really helped me find my creative inspirations and passions. I met so many talented people and I wanted to document that. In fact, I originally moved back because I wanted to be a tattoo artist. Slowly I found my way into social media marketing, and then I got deeper into photography and graphic design from there.

“I don’t have time to be distracted as heavily as the internet would like me to be.”

You mentioned working at a Panera Bread in Texas to save up money to move back to CA. Do you feel jobs like that make you appreciate where you are now even more?

Yes! That was the only job I ever worked in food service and direct customer service. I think I worked there six months or so when I first turned 16, and it was … not fun. I looked at it as a way out. Except, instead of saving any money, I would just spend it all on spray paint and paint supplies. I loved painting. I still love painting, I just don't do it as much. Eventually when I did move [back to California] … I was still broke. But … it’s okay. [Laughs]

Tell me about the spray painting. What kind of art did you do?

When I lived in Texas, there was nothing for me to do there, but I found a group of friends who did graffiti and I really enjoyed that. Shouts out to my art teacher junior year of high-school — she let us hang out in the back of her classroom, where there was a big couch. All the graffiti writer kids would hang out and hide our supplies there. At our school if you got caught with paint markers and things of that sort, they would possibly give you an in-school suspension or bootcamp. Except we found a drawer in that classroom that only we had the key to, so we were able to keep all our stuff locked.

Senior year, when I moved back to LA, the artist at the tattoo shop asked me, “So, do you paint anything else besides letters?” I kind of shrugged my shoulders, I guess, so he just gave me a bunch of Sailor Jerry prints to trace. [Laughs] If you’ve ever seen American traditional tattoos, Jerry is kind of the originator of all that. Him and Ed Hardy. At a tattoo shop, you just trace. You get tracing paper, and if you wanted to learn how to draw, you start by tracing other people's work until you kind of create muscle memory from it. Eventually you learn to draw on your own.

Going from watercolor, to spray-painting, to tattooing, to graphic design and marketing, to film photography — that’s an array of creative talents, to say the least. Are there any lessons you’ve learned from those transitional years?

Those transitional years, they’re what make or break a photographer, or any creative. There's a point where you're inspired by something, and you want to make something like that, but your creative ability doesn't necessarily match that. So you get down on yourself. It's easy to give up.

What no one seems to grasp is the person you're inspired by probably took years of trial and error before they could do that. Comparison's huge in the creative community, especially nowadays with social media and the possibility of like seeing, for example, a 22 year old go from zero to a million followers within a week because of some crazy work that they did. But … they probably worked on that for a while. Everyone talks about overnight successes, but the reality is people work for years before they get to a point where they’re making work that’s up to their own standards. To give up on yourself in those transitional periods when you're learning something, and you haven't fully mastered it yet, it's a slap in the face to your own creative ability.

For example, when I first started out, I was shooting digital. I never liked what I made. I would sit down to edit my photos for hours — literally for 4 or 5 hours after a long shoot — and it would just never happen. Eventually I started to have this realization of, “Hey, the photographers you look up to aren't shooting digital — they're shooting film! Your inspirations are film photographers and you're shooting digital?! There's no way you're going to be able to replicate those colors, that feeling.” I always had a feeling for film, so I started lean into it more heavily after that point.

“I don't view other photographers as competition — I see them as other people.

My only competition is being a better creative than I was a year ago.”

So it’s a matter of grinding even in those times when it seems like you’re missing the mark and falling short of your inspirations. I definitely understand that feeling. What’s the best way to just go ahead and practice? What’s helped you push through those thousands and thousands of images to get to the kind of work you produce these days?

Being intentional. Asking myself the questions: “Why am I making this? What am I making this for? Who is this for? Am I going to really enjoy this piece? Why am I going to make this piece of art?”

When I started shooting film, I realized I have 36 photos. Whether it’s me, as a photographer, or the model, or someone who hired me … someone has to pay for that film roll, and then for it to be processed. So why not try to make the best out of each frame?

Even with digital [photography], you pay thousands of dollars to start, so why not be intentional? It’s okay to try things. It's okay to experiment and yourself a reason. “I'm making this because I want to experiment with fashion photography.” “I’m making this because I want to experiment with harsh light.” Let's get down to why we're really doing it and then really lean into that as opposed to just guessing.

When it comes to that comparison, especially on social media, how do you stay above all that to stay grounded in what you’re doing?

Followers, money, cars, clout … it's extremely easy to get lost in all of that. But for the most part, I'm really happy for the people who’ve reached that level. And frankly, I’m not where I want to be just yet, so I don’t have time to be distracted as heavily as the internet would like me to be.

I’ll get these comments like, “Oh, I wish I had your life.” And I'm like, “… I just work all the time. It’s really not that interesting.” I make photos and the photos are interesting, sure, but personally I’m either shooting, driving, sleeping, or editing. It isn’t all that. Instagram is just a highlight reel of people's lives. And beyond that, it’s not even a highlight reel of their actual lives — it's a highlight reel from the artificial life that they've shown to people on the internet. It's all a facade of what the internet thinks you should be doing.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of feeling like, “I should be there,” and “I should be doing this.” I have to fight that by realizing that at the end of the day, my only competition now is being a better creative than I was a year ago, being a better creative than I was a month ago. If I learned something new within a week, if I’ve done a shoot with another client, if I’ve accumulated a body of work over the last year that I think is better than what I did the year before … that’s a success. So why am I going to compete with others who are on their own path? We don't have the same life! My life is mine. As long as I can make work, I’m good. I don't view other photographers as competition — I see them as other people. I just see people doing what they love.

What’s a typical day look like for you as a film photographer?

Let’s take this past Saturday, for example. I'll get a bag together the night before, and since I’m going to be shooting at a studio, I’m going to need specific types of film, maybe portrait 100 or 400 for inside. When I’m going outside I’ll take a pro image 100, and if I'm going to be shooting at night, I’ll carry a flash and some 800 film. I'll literally pack a bag of maybe three or four cameras. If I don't finish a roll on one camera, I have another camera to load.

On set, I'll set up my bag, sit down, and break down exactly what I'm shooting. Depending on what I'm shooting, I always have a comfort meeting to check in with the model and ask those questions: “What are we shooting for? Why are we doing this? Where are you going to put the photos? What do you think you need to get out of this? And do you have any poses or anything that you really want to get out and do?” And then, “What's your level of modeling experience? Have you done a lot of modeling before?” I have to figure all that out beforehand. I'll repeat that whole process as many times as I’m shooting, and then at night I put all the film in a bag, drive to one of my labs, and then drop it off in the little drop-off window. Then I wait until until the next day when I can get it all back, edit, and send the photos off to clients.

How do you build those business relationships with clients?

I let them happen organically. If they happen they happen. For the most part, I let people come to me. I'll DM individuals, and companies, from time to time, and sometimes you hear back sometimes you don’t. It’s cool either way. Every now and again I'll have a random company reach out and be like, “Hey, we want you to make photos for us!” And then another company will reach out saying, “Hey, we just saw what you did with them. We want to work with you too.” It’s what’s going down in my DMs right now: I'm sending off a mood board for a company that wanted to hire me because they saw my work for the Tyga BTS shoot.

I do believe the universe has a plan for you as a creative. Obviously you have to put in the work for it, but if you do … you will get noticed. I'm not good at forcing relationships. I take it as it goes and if people want to come work with me, great. If they don’t, I'll just recommend ‘em to another photographer. You always want to end things on a positive note, no matter what the interactions were like. What you put in is what you get back, at the end of the day. The universe is going to notice.

The Tyga BTS shoot for Vixen sounds like a fucking blast. Can you remember any other shoots or gigs that you really enjoyed?

I really enjoy the shoots that are less serious. Recently we just said, “Let's get three photographer friends and six or seven models in a studio for a day and just shoot hella photos!” Those are great because you get to see other people making work — it’s a creative environment. I also really enjoy the shoots when I get to work with a model who hasn't modeled before, but by the end of it, she's like, “I'm ready to do another shoot whenever!” I take that as a great honor because they're coming in with an attitude of, “I've never modeled before, and I'm honestly not sure how to do this, but I am comfortable with you taking my photos.” That's huge, right? The best feeling is when you see a model go from kind of nervous to … flourishing a little bit.

I loved the caption of one of the photos you posted on IG: “I just be listening to Jaden and Mac Miller and watching videos all day sometimes.” What's your favorite Mac Miller project?

Watching Movies With the Sound Off. I bought the physical CD with my own money after working at Panera for a month. It had just come out, so I went walking down the street to Target and bought it with my second paycheck ever. My favorite song off that is ‘Objects in the Mirror,’ the live recording that he did with the Internet, for the Space Migration Sessions. That’s my favorite version.

You're a legit Mac Miller fan.

I feel like you can see a lot of his later work in his earlier work. It’s a huge transition, and I like to analyze all that. In ‘Knock Knock,’ he's talking about the future, wanting to have all this money and be ballin’, and how great things are going to be then. Then you have a song like ‘2009,’ which is the exact opposite: the mood is, “I have all this money now, but I ain’t got nobody.” It’s interesting to me to see those comparisons and contrasts.

I actually have two whole seasons of his MTV show on a hard drive on my computer. There’s a hilarious scene where he signs [one of his alter egos] Larry Lovestein, to a record deal. He’s wearing a tie-dye t-shirt with a hockey style Jersey thing, platform boots, and an afro wig, and he talking about how the music he makes is “yazz” with a a “soft ‘azz.” It’s all 70s-inspired, and he’s interviewing himself, Mac on one side, Larry on the other. So funny. [Laughs]

It’s like a darker version of the afro wig he wore in the Frick Park Market video?

Yeah! I was just thinking about that, because I realized Mac’s the reason I bought a white Polo hat at one point. It was what he was wearing in the ‘Frick Park Market’ video. That was back when everyone wanted to wear Diamond Supply Co.

Now that I think about it, he really owned that era of clothing and fashion. Obviously people think of Pharrell and Kanye, but for me, personally, Mac inspired a lot as well. When [those first few Rex Arrow videos dropped] you would see people with the exact same, or very similar fits: the baggy, sagged blue jeans or khakis, the black crew neck sweatshirt, and the snap backs or Polo hats. Maybe some Nike SBs.

Tell me about the film photography renaissance. What’s it like to be part of that and how has it affected your work and career?

I love the fact that it's becoming popular, but I also hate it. I love it because so many people are finding their first film camera and discovering an interest in photography. Personally, I fell out of digital photography, but then once I picked up that film camera again, it was something totally new. I want other people to be excited about it like I was. I really enjoy people finding their own process and time with it.

On the other hand, since film cameras aren’t produced any more (other than a Leica, which is like $5000), everything’s going up in price. I remember I got my first film camera for $5, my second one for $10, and even three years ago, I got one for $20. These days that same camera’s running between $150 and $250. It’s just following the laws of supply and demand but … it's frustrating.

The other upside is with film labs. I used to go to film labs and they'd be like, “Oh yeah, we're closing down for good.” Nowadays it’s the opposite: Going out to Relics in Long Beach, hearing about Redroom in Van Nuys, seeing Kodak releasing, or reproducing, new films again. It was really something that was dying for a while, and I used to have clients who didn’t understand the difference between digital and film. But it’s changing — these days I have people who come to me specifically for the film.

Personally, I’ve probably put more than a dozen people onto getting their first film camera. I'm always stoked to help people find their first film camera and answer questions. I don't understand anyone who tries to gatekeep it. We're all photographers. We're all just trying to help each other out here. I want to see it flourish and continue to grow as I try to flourish.

Final question: given your Instagram handle, what’s your go-to coffee order?

Large cold brew with a splash of oat milk and a little bit of simple syrup. I go to Bluestone Lane, and also this local coffee shop that I don't know the name of at The Hangar in Long Beach, pretty much the only coffee shop there. And then occasionally if I'm running late, I’ll hit up a Starbucks and down one of their vanilla sweet cream cold brews. [Laughs]